BOKEH for landscaper

by Christopher O'donnell

You may have heard other photographers speak of “bokeh” when discussing the depth of field in their images. If you haven’t, then this article will be especially beneficial to you. Many photographers use their aperture to isolate their main subject (if you’re not sure what it means to use your aperture, this article here will help explain things). The desirable benefit of this is creating a stunning image with a soft, abstract-like background and/or foreground, as seen in the photo below.

This photo was taken at f/1.4, which gave a soft and dream-like background to this dandelion.

Before I get into the specific techniques on how to capture an image like this, I want you all to have clear idea of what exactly bokeh is.

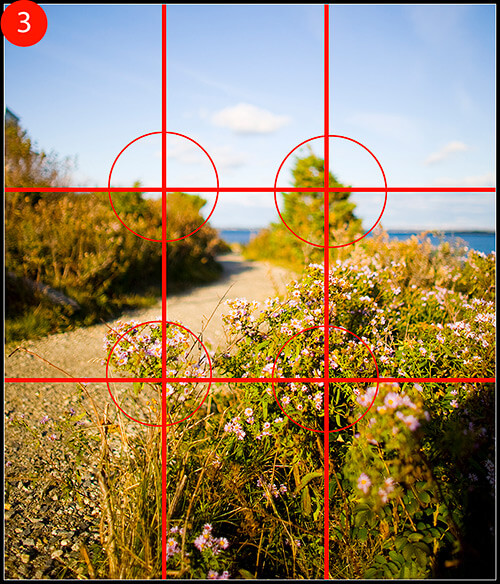

Bokeh is not just having a shallow depth of field – or a blurred background/foreground – it is the quality of the blur. While the interpretation of what constitutes “good” and “bad” bokeh depends on your own personal preference, there is a general understanding that an image with good bokeh is one that has a lot of variations in shapes, color, and texture – such as the image below.

This image was shot with a telephoto lens in order to compress the distances between the foreground (the hill), the middle ground (the yellow daisies) and the background. As you can see I’m sticking with a dandelion theme.

While a shallow depth of field was used here, the bokeh is very smooth in the blurred background (the sky, horizon line, and water). Instead, the more defined, coarse bokeh here is the shapes and colors created by the out-of-focus dandelions in the immediate foreground, and the yellow daisies and small tree present in the middle ground. Rather than being in perfect focus, they create beautiful overlapping shapes.

So a photograph that has a very flat blur or is just simply out of focus (like the background water and sky in the above image) is not something you would generally consider to have good bokeh.

Identifying an image with strong bokeh will come easier with practice and you’ll soon develop your own personal taste. For now, let’s focus on how to actually take an image with bokeh.

Having beautiful bokeh in your photo is much more than shooting with a wide aperture – there is a recipe for it.

Besides widening your aperture (also referred to as “opening up your lens” or “stopping down all the way”), the distance between you and your subject and your subject to your background greatly affects the amount of blur you have in your image – thus determining the quality of your bokeh.

For example, if you’re using a regular portrait lens – say a 50mm prime – to capture an image of your friend, you’ll notice some considerable differences in your bokeh depending on the distance between your friend and their background. If you were to place them in the middle of a field with the closest background object – say a line of trees – about 100 ft. away, you’ll be able to capture a very blurry background.

In contrast, if you were to place your friend right in front of the tree with only a foot or so between them and the background, you’ll have little to no background blur. For successful bokeh, you will need to have some space in between your subject and your background. The exact distance of the space needed greatly depends on your focal length, the distance between your camera and your subject, and of course the aperture you’re using. The only way to know the exact distances for good bokeh is through practice and experience.

The same goes for the distance between you (meaning the camera) and your subject, only reversed – the closer you are to your subject, the more profound your background blur and bokeh will become. Let’s use the same example of you and your friend again. Instead of focusing on how much distance is between your model and the background, open up your lens all the way and gradually approach them, making sure to take photos along the way. When comparing your photos you’ll notice that your background will become more and more blurry – or develops a more shallow depth of field – when you approach your model.

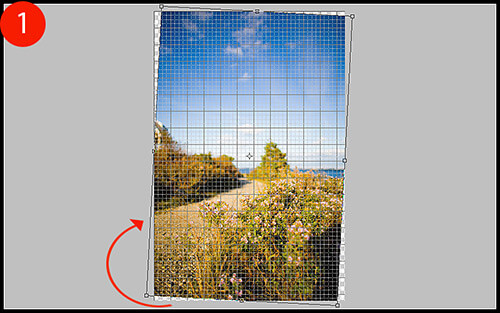

This is why wide angle lenses work so well in landscape photography – especially ones that have wide apertures. The ability to get very close to your subject while still capturing much of your surroundings can create a dramatic and stunning perspective:

The immediate foreground of this image was only a few inches away from the camera lens, yet I was still able to capture a large amount of my surroundings. Not only did this wide angle lens allow me to capture a wide area, but it gave me stellar bokeh since I was so close to my focal point (the leaves in the foreground).

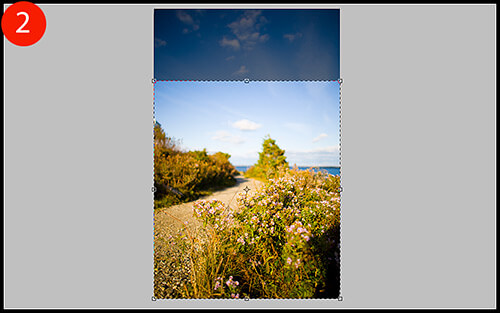

It’s important to be able to balance your aperture with the distance between your subject and the background since it’s possible for you to go too shallow with your depth of field which will actually smooth out any defined bokeh shapes you may have had.

For example, let’s look at the first image of the dandelion again.

You’ll notice that the foreground has some identifiable bokeh around the grass and flowers, but the background is blurred to the point where defined bokeh shapes is non-existent. Instead, it’s a blanket of blur because the image was shot at f/1.4 – which, for this particular image, is an aperture wide enough to smooth out any shapes in the distant tree line and sky. In other words, my focal point is too far away from the background at this aperture to create any well-defined bokeh.

While the soft background works particularly well in this image, it may not be something you’d want for others. A smaller aperture would have produced more bokeh in the background, but the dandelion in the foreground would not have been as isolated. You’ll often encounter these delicate balances when shooting so it is inevitably up to you and how you want to create your photo.

So to summarize, the two biggest factors in controlling your depth of field (besides, of course, your aperture) are:

1. The distance between YOUR SUBJECT and the BACKGROUND

and

2. The distance between YOUR CAMERA and YOUR SUBJECT

However, your distances are only part of the puzzle. The steps above simply help you to adjust your distances as necessary in order to get the right depth of field to create bokeh – you still need a source of bokeh. You can have a very shallow depth of field and still have no bokeh depending on what your background (or foreground) consists of.

The quality of your bokeh has everything to do with what elements are in your image. The wonderful shapes and patterns created by your lens are made from points of light that are then transformed into bokeh. These points of light could be a variety of things – reflection in the water, light coming through leaves in a tree, or even a bright light reflected on a surface.

Let’s look at some bokeh examples that illustrate my point here:

While there are no direct sources of light in this image, the sun is reflecting on the side of the boats. This reflection created the great bokeh shapes you see. Notice how the bokeh is only on the side of the boats that have the sun’s reflection while no bokeh is present on the shadow side.

The bokeh in this photo is a bit different. The bokeh here is created from the direct sunlight coming through the leaves and also hitting the ground. This combination of bright bokeh with the darkened environment of the forest is a striking contrast.

The final image shows that no matter what depth of field you use, you can’t create bokeh without a point of light. I took this photo on an overcast day, which means no reflections and no sources of light. Although I shot this at f/1.8, there is no bokeh present anywhere in this photo. I enjoy the stark mood created by the smoothness of my blur, but if you’re looking for bokeh then you need to follow the light.

To create a great, bokeh-filled image, you have to first get in the right position to create it by adjusting the distances between you and your subject, and your subject to your background. When you have that technique down, you can then judge the quality of your bokeh before ever taking your photo just by seeking out strong light points in your image.

Remember: a great photograph does not have to have bokeh in it. However, it’s a unique phenomenon in photography that you can fun with