When you are strolling down the poultry aisle, did you ever wonder about the history of the bird that is shrink-wrapped into that tidy little package?

Have you ever wondered about the role chickens have played in the lives and culture of humans worldwide?

Chances are you have not been preoccupied with these questions.

But the answers expose a dark blanket that has been pulled over the eyes of society, hiding the truth about what an amazing creature the chicken is and it’s special gift to humankind: the egg.

Eggs are even more revered by the French than by Americans, as Chef Stacpoole so passionately extols in the above quote. After all, how could you make classic French dishes like crepes, soufflés, quiches, or a sauce Béarnaise without a pantry full of farm-fresh eggs?

And where would your Coq Au Vin be without a fresh bird for the pot?

The story of the common chicken is one that begs to be told, especially in this age when people generally underappreciate where their food comes from, much less its history. I think we should occasionally stop to revisit tales that are all but forgotten, renewing our appreciation for the things that helped us get to where we are.

This is my reasoning for writing this article, which I’m sure you will find rather different from my usual musings.

Americans have been the unfortunate victims of manipulation by government and industry on so many issues, and when it comes to poultry, we’ve been convinced that chickens are dirty and stupid and natural vectors of disease.

Nothing could be farther from the truth.

Which Came First? British Scientists Now Say it was the Chicken!

Which came first, the chicken or the egg? The age-old riddle that has stumped us for generations has finally been laid to rest.

In February of 2010, British scientists reported that a protein found only in a chicken’s ovaries is necessary for the formation of the egg. According to scientists, the egg can only exist if it has been created inside a chicken. This protein is fundamental in the development of the shell.

Of course, you may be wondering, if the chicken came first, then where did it come from?

Leaving that mind-bender for another day, let’s explore where your poultry comes from.

Poultry Products Run “Afowl”

Although chickens and eggs from the best sources offer exceptional nutrition, many obtained from your grocer range from nutritionally bankrupt to downright dangerous.

In 2007, it was found that 83 percent of fresh, whole broiler chickens bought nationwide contained campylobacter or salmonella, the leading causes of food borne disease. Prior studies have shown that organic chickens are far less contaminated with these antibiotic-resistant bacteria.In fact, conventional chicken products were found to be up to 460 times more likely to contain antibiotic-resistant strains than antibiotic-free chicken products.

Factory Poultry Farming

So the precautions about carefully cleaning surfaces that the meat touches and carefully cooking it are well placed. But please remember that these are factory farmed conventional chickens. Locally grown chickens raised healthy have nowhere near these infection rates.

But the question remains, can you really trust advertisements that claim chicken to be antibiotic-free?

Tyson Foods was ordered by a federal judge to withdraw its “raised without antibiotics” ads when it was discovered they were injecting eggs with antibiotics and using antibiotics in their feed.

There are similar problems with commercial eggs.

Eggs from large flocks (30,000 birds or more) and eggs from caged hens have many times more salmonella bacteria than eggs from smaller flocks, organically fed and free-ranging flocks.

The lesson here is, the closer you can get to the “backyard barnyard,” the better. You’ll want to get your chickens and eggs from smaller community farms with free-ranging hens, organically fed and locally marketed.

This is the way poultry was done for centuries ... before it was corrupted by politics, corporate greed and the blaring ignorance of the food industry.

Move Over Chickens — Here Comes the Automobile

Prior to the 1920s, poultry was raised for fun in the United States, mostly as a hobby, but not so much as a food source — the fact that you could eat them was incidental.

Backyard Henhouse

National Geographic Magazine, April 1927 and The Food MuseumBackyard “poultrymen,” as the April 1927 National Geographic article calls them, gradually disappeared after World War I.

Chicken coops were replaced by automobile garages as post-war mechanization took over, and chickens began to be regarded more as livestock.

Henneries became commercialized operations capitalizing on poultry’s economic value as a human food.

Chickens saved the day for thousands of farmers in the Midwest who suffered crop failures, labor shortages, and price drops, and who were unable to make a living. Chickens were, and still are, very efficiently “manufactured” from raw material — a four-pound hen consuming 75 to 80 pounds of feed will produce 25 to 30 pounds of eggs!

In 1927, most flocks consisted of 50-300 birds. But flocks didn’t stay that small and cozy for long.

By the 1940s, the chicken population in every American city was roughly half that of the human population. Most people obtained their eggs from their own back yard, or from a neighbor or a farmers market down the street.

What happened to the backyard poultry farmers?

They bought cars and built garages.

Industrialization Creates the Poultry Factory

Profits grew as the nutritional value of eggs was recognized — they were cheap, easy to digest, and had high quality proteins and fats.

In henneries, incubators replaced brooding hens so the hens could quickly get back to business laying eggs.

Colony brooders, heated by coal or kerosene, held between 300 and 1,000 chicks under each stove — and between 10,000 and 15,000 chicks could be raised in one brooding cycle.

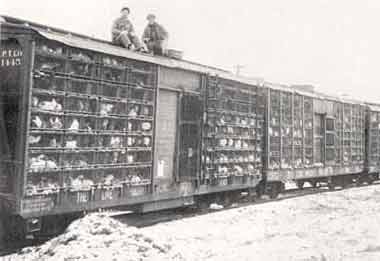

Live Poultry Train, USA (1920s)

United States Department of Agriculture and The Food MuseumThis mass production gave rise to the shipping of baby chicks by the thousands, all across the country, in cotton-lined wooden boxes with holes punched in the top for ventilation. The bottoms of the boxes were lined with excelsior to “give chicks a toehold” and prevent them from sliding about during their journey.

Artificial lights extended their laying cycle.

After World War II, automation of farms became commonplace. Conveyers, cartons, refrigeration trucks, etc, meant more eggs could be produced and delivered to the masses.

As a result of predators and climatic variation, chicken mortality rates were a dismal 40 percent annually. Hens were moved indoors, which improved the health of the birds and decreased losses due to predators.

Mortality rates decreased to 18 percent per year.

But problems developed with sanitation, waste control, and pecking/aggression. Parasites became a problem with the birds in close quarters, so medications were developed to combat these.

In the 1940s, Ohio State University developed “the Cage System” where a raised floor meant the hens weren’t in contact with their waste. Feeding was more reliable because timid hens got as much to eat as more aggressive hens, since they were separated.

Health was better, and mortality dipped to 5 percent.

Fans were added to cool hens off in the summer, and body heat from hens huddled together in winter kept them warm. Growing automation allowed production of larger and larger numbers of eggs. Automatic egg washing, sonic probes to detect cracks, and sensors to candle, weigh, and grade eggs by the masses replaced completing these tasks by hand.

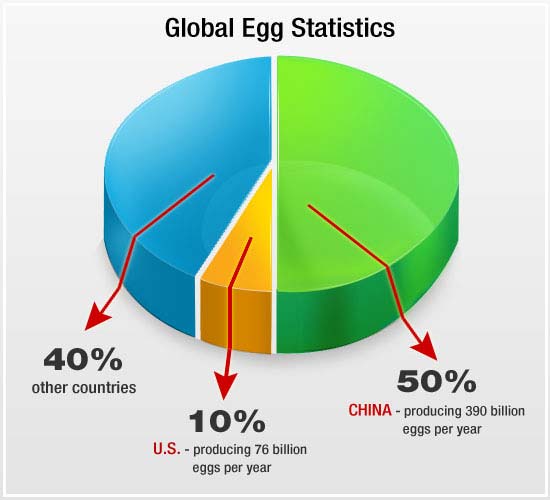

Now the U. S. is producing 76 billion eggs per year, which is only 10 percent of the world’s supply. China is the largest producer, yielding 390 billion eggs per year, which is half of the world’s eggs.

Now, hens are often crammed into tiny quarters with less space to stand upon than the computer screen you are looking at. Disease is rampant, and the birds ARE filthy — not because of their nature, but because we have removed them from their natural habitat and compromised their innate resistance to disease.

Their lives are cut short by greed and shortsightedness.

Hens who could live to be 20 years old are crippled and sent to slaughter as soon as they exceed their laying prime. And today’s eggs are a pale substitute for the little nutritional dynamos of yesteryear.

Chickens Were Actually Used As Currency

In the words of Janet Fischer, one of my valued readers who has been involved with poultry for 45 years and is well versed about property rights regarding chickens:

“It is too bad that playing politics with food has resulted in chickens being demonized and the public dumbed-down to benefit big business. It might surprise most people that unalienable rights to keep chickens, even in the city, are still on the books, yet revisionism in our public schools has removed almost all this knowledge, along with notions of economic independence, tools for critical thinking, and knowledge about civics or free country.”

She points out that there are laws still on the books valuing chickens as vital agricultural commodities, which can be traded or sold. In fact, chickens and eggs were used as currency during the Great Depression!

Did you know the federal penalty for theft or destruction of one chicken is $5,000? The federal government affords you the same protections for chickens as for other personal property, like your house or car.

Yet sadly, most American children think chicken comes from the grocery store.

The skill of raising chickens has been removed from public knowledge, and chickens are now portrayed as stupid, filthy animals riddled with disease that should be hidden in dark warehouses, out of public sight.

Gone is the knowledge that chickens will thrive and be clean and healthy if provided basic access to the ground for bathing and scratching, access to clean water, and a safe roost to fly up to at night.

Backyard chickens and their eggs will not suffer the same cross-contamination found in large commercial plants, and if managed properly, these birds will not get sick from stress.

Where Should You Get Your Eggs?

Hen laying an egg

Many of us will simply be unable to raise our own chickens (although I’ll provide some helpful guidance on how to get started at the end of this article, for those who want to give it a try) so the practical question is, should we just purchase organic eggs from the grocery store?

I strongly believe that this is NOT your best choice.

The key here is to buy your eggs locally. About the only time I purchase eggs from the store is when I am traveling or for some reason I miss my local egg pickup.

Fortunately, finding high-quality organic eggs is relatively easy, as virtually every rural area has small farmers with chickens. If you live in an urban area, visiting the local health food stores is typically the quickest route to finding high-quality local egg sources.

Without question the single best source you can find is a local farmer who is raising their chickens humanely and not in a factory farm. The chickens should be allowed outside and eat insects. If you find these eggs the yolks will be bright orange due to the increased nutrients.

Next best would be organically-raised, but NOT omega-3 eggs, as they will likely have rancid omega-3 in them. The chicken should also be free range. But please remember that eggs from local farmers are nearly always superior quality, and fresher.

Farmers markets are another great way to meet the people who produce your food. With face-to-face contact, you can get your questions answered and know exactly what you're buying. Better yet, visit the farm -- ask for a tour. If they have nothing to hide, they should be eager to show you their operation.

Your egg farmer should be paying attention to proper nutrition, clean water, adequate housing space, and good ventilation to reduce stress on the hens and support their immunity.

Cooked, or Raw? And the Issue of Salmonella…

The CDC and other public health organizations will advise you to thoroughly cook your eggs to lower the risk of salmonella, but eating eggs raw is actually the best in terms of your health.

It’s important to realize that salmonella risk comes from chickens raised in unsanitary conditions. These conditions are the norm for factory farms, but extremely rare for small organic farms. In fact, one study by the British government found that 23 percent of farms with caged hens tested positive for salmonella, compared to just over 4 percent in organic flocks and 6.5 percent in free-range flocks.

That said, you are clearly better off seeking eggs from only high-quality sources, which are the ones that will be safe from the get-go, and then consuming them raw, which is their most nutritional state.

For more tips on eggs, including how to identify fresh, high-quality eggs, please read Raw Eggs for Your Health.

And, for more information about salmonella from eggs, please review yesterday’s article on this topic.

A Bit of Chicken Lore

The hen has been a companion of man for many centuries.

Wild chickens originated in India and East Asia (China, Thailand, and Vietnam) and appear to have been domesticated around 7000 B.C., simultaneously in China and India.

Chickens spread to West Asia around 2500 B.C., and on to Africa and Egypt thereafter.

Chickens reached North and South America in the 1500s along with Spanish explorers and were reportedly part of the Mayflower cargo.

Ancient peoples regarded fowl as sacred [i] .

In 300 B.C., a verse went that four lessons could be learned from the cock[ii] :

- Fighting well

- Getting up early

- Eating with your family

- Protecting your spouse when she gets into trouble

The Greeks and Romans often sacrificed chickens in religious rituals. In many cultures, fowl were believed to hold mystical qualities.

For example, it was believed that you could get rid of your bad habits by drinking a solution made from dried cockscomb. And you could enhance your virility by applying a mixture of cock’s blood and honey.

Cockfighting has, unfortunately, been a major part of the chicken’s history, including being a popular pastime in England during the reign of Henry III.

The first poultry shows were held in the U.S. (Boston) and England in 1949, which sparked an interest in creating new and interesting breeds of fowl.

“His Majesty of the Barnyard”

Onagadori Chicken

Long-Tail FowlThe affection we humans feel for chickens is obvious in the caption chosen by M. A. Jull, Ph.D. for his April 1927 National Geographic Magazine article “The Races of Domestic Fowl.”

The opening photo is captioned, “His Majesty of the Barnyard.”

And majestic they are!

There are now hundreds of different breeds of chickens. The different breeds are classified by size, origin, primary use (eggs, meat, or exhibition), skin color, earlobe color, egg color, plumage, personality traits, and even crowing patterns.

Some of the most notable and unusual breeds include the following — although there are many, many more:

- Onagadori (“Honorable Fowl”): Originating in Japan, this breed is known for its incredible tail plumage, sometimes reaching twenty to thirty feet long! This is the patriarch of Japanese poultrydom. Kept in special cages in which the feathers of their tails are rolled up in a bundle and suspended on the walls for protection, the Onagadori’s tail feathers grow rapidly and never molt.

- Sultan: This fancy feathered breed from southeastern Europe sports a full crest, muff and beard, and feathered shanks.

- Bantam: One of the oldest breeds, bantams are the miniatures of the chicken world. They are very quick and spunky.

White Sultan

My Pet Chicken- Silkies: Silkies are one variety of bantam that look like they have hair instead of feathers.

- Frizzles: A frizzle is a mutant chicken whose feathers curve outward, instead of lying flat against the chicken’s body, giving rise to a “fluffy,” mussed up look suggestive of a bad hair day.

- Long-Crowers: These unusual roosters can continue to crow for as long as 20 seconds. If you live in the city and are considering a small flock of fowl for your back yard, this might not be the best way to impress your neighbors. To hear a few of these cocky callers, turn up your volume and click here(WARNING: May cause odd looks from nearby pets and officemates.)

Chickens are actually part of the pheasant family, which is divided into four subfamilies based on how the tail feathers molt. In chickens, the tail molt is centripetal (from the outside to the center), so they were placed in the subfamily Phasianinae and genus Gallus, meaning “comb.”

The color of a hen’s feathers and earlobes determines the color of her eggs. Brown eggs are nutritionally the same as white, and taste identical.

Insights from a “Chicken Whisperer”

In an effort to learn more about raising chickens from a “backyard” chicken farmer, I interviewed Maureen Woodcock who, along with her husband Bill, raises a small flock of 8 to 20 hens in northwest Washington State.

Bill is known to his friends as “the Chicken Whisperer.”

Maureen and Bill built a small henhouse that is connected to a fenced chicken run that merges with a stream in the woods where the chickens roam freely. The birds are free to forage by day, scratching in the dirt and eating grasses and bugs, and even drinking from the stream. And then they retreat to the coop for the night.

The coop has a gravity watering system, so the birds have access to fresh water at all times.

For heat, only one 100-watt light bulb is required 99 percent of the time, even in the winter. In addition to providing a little warmth, the light from the bulb gives the birds a bit of extra winter daylight to keep them laying eggs 365 days a year. They average one egg per chicken per day, every day, at least while a chicken is in its laying prime.

Their free-ranging diet is supplemented with kitchen scraps and a little natural grain feed.

Maureen said they’ve never had any problems with parasites or other diseases. The birds’ feet get cleaned by scratching in the soil and running around in the forest. Their diet is so varied that their immune systems are in tiptop shape, so they simply never get sick.

The remarkable thing is, as soon as they acquired the chickens, other wild birds began moving in. Maureen cheerfully says, “Birds attract birds.” Before long, they had drawn a wild peacock, several ducks, and a blue heron — a natural aviary!

So, how about raising your own?

A Few Thoughts about Raising Your Own Chickens

If you are fed up with the quality or availability of eggs in your area, you may want to consider a backyard barnyard. Beyond the obvious advantage of a continual supply of wonderfully fresh eggs, there are other advantages:

- Chemical-free bug and weed control

- Manufacturing of the world’s best fertilizer

- Living sustainably

- Improved compost from chicken poo and egg shells

- Saving a chicken from a factory-farmed life

- Fun and friendly, low-maintenance pets with lots of personality

If you are interested in the possibility of raising a few chickens yourself, a good place to begin is by asking yourself a few questions:

- Can I dedicate some time each day? According to My Pet Chicken , you can expect to devote about 10 minutes a day, an hour per month, and a few hours twice a year to the care and maintenance of your brood.

- Do I have enough space? They will need a minimum of 10 square feet per bird to roam, preferably more. The more foraging they can do, the healthier and happier they’ll be and the better their eggs will be.

- What are the chicken regulations in my town? You will want to research this before jumping in because some places have zoning restrictions and even noise regulations (which especially applies if you have a rooster).

- Are my neighbors on board with the idea? It’s a good idea to see if they have any concerns early on. When they learn they might be the recipients of occasional farm-fresh eggs, they might be more agreeable.

- Can I afford a flock? There are plenty of benefits to growing your own eggs, but saving money isn’t one of them. There are significant upfront costs to getting a coop set up, plus ongoing expenses for supplies.

No comments:

Post a Comment